2020 will be remembered as the year that education changed forever — or, at least it should be.

With 90% of students globally unable to attend classes in person and teachers switching to holding classes via Zoom, WhatsApp and Microsoft teams, the sector can no longer hide from the urgent need to digitise and embrace technology. Now more than ever, it’s evident that, if deployed properly, technology will be the key enabler to offset the potential widening of inequality in education caused by Covid-19.

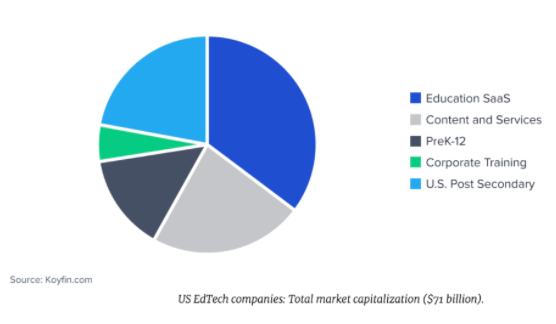

Whilst EdTech is certainly not a new market, in recent years the sector has seen increasingly more capital being allocated to it: in 2018, around £90m was invested across 50 EdTech companies in the UK alone (a 140% increase from 2016). In 2019, $1.7bn was invested in EdTech companies in US, seeing $7bn worth of investment globally, entering the new decade with 14x more capital than the previous. Even in later stage companies, we’re seeing dozens of private equity funds being created and deployed solely to invest in the sector. The industry expects to see over 100 education companies with $1bn+ market capitalisation by 2025, despite the fact that the US currently has only 29 publicly traded companies (which total $71bn market cap).

A lot of room for growth …

In that sense, it’s no wonder that investors at all stages are turning their attention to the industry: the sector has gone from being valued at $56bn in 2016 to $175bn in 2020, and is expected to reach $420bn by 2025, growing by 15% CAGR.

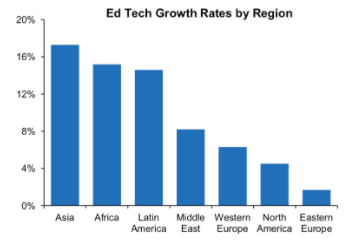

Though the majority of EdTech investment has been in the US, according to AGC, China and India actually represent the fastest growing markets [1], which you may expect given the relative population growth rates. Vast and fast-growing populations call for modern ways of incorporating technology to provide education to the population en-masse. In a similar vein, Asia is closely followed by Africa and Latin America in terms of growth rates by region.

Source: AGC Parters, Insights, January 2019

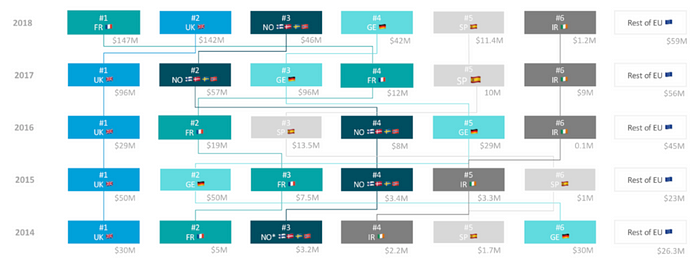

Europe is catching up, too. Between 2014 and 2018, the continent saw $1bn invested in EdTech companies, with a record high $450m in 2018 [2]. While the UK and the Nordics have historically dominated the market, Germany, France and Spain are emerging as new leaders in the sector.

Source: BrightEye Ventures, EdTech funding in Europe, 2014–2019

Nonetheless, EdTech is hugely underrepresented in the total global expenditure on education. The education industry has historically seen very little digitisation, with just 2% of education being focused on digital. In 2016, the US spent 7% of its total GDP on education — a stunning $1.4tn — but education technology currently still represents only 5% of spend on education globally. Given the detrimental impact of Covid-19 on education across the world, it’s no wonder that industry experts anticipate now to be the tipping point for EdTech. Covid has forced even the most stubborn players to modernise and digitise, and the longer we stay in this environment, the harder it will be to revert to the way we used to do things. Students and teachers alike are also generally now tech-savvy enough to use and benefit from the numerous technologies that are available to them in the classroom.

It’s worth noting that what we refer to in this research as the education sector is actually a multitude of smaller segments of education that are ultimately very different from one another — pre-school (Pre-K), primary and secondary schooling and sixth form (K-12), higher education and corporate learning.

There are three sets of challenges that explain why EdTech represents such a small proportion of the global education market.

Numerous stakeholders

Relative to other industries, the education sector has a multitude of stakeholders: teachers, students, local authorities, policy makers, parents, administrators, faculties, recruiters and employers. The more stakeholders, the harder it is for an EdTech company to find the right business model. This explains why so many companies are resorting to Freemium models [1], offering a free version of their products and hoping to monetise by up-selling a ‘Pro’ subscription to the most engaged users in order to avoid the potential lengthy B2B sales cycles.